Source: The Guardian

Philip Oltermann in Berlin

@philipoltermann Fri 16 Dec 2022 13.48 GMT

Show takes a deep dive into story of 1922 film that spawned an entire genre – with free entry for blood donors

It was a nightmare born out of a pandemic: a silent killer that arrived from a faraway land, rapidly spreading a delirious fever across the domestic population and leaving its hosts in an anaemic stupor.

By channelling contemporary fears around infectious diseases in the wake of the 1918-20 influenza pandemic, the 1922 expressionist masterpiece Nosferatu founded an entire genre of vampire horror movies and inspired claw-fingered monsters that would spook generations to come, from Freddy Krueger to the Babadook.

A hundred years after its commercially ill-fated release, a new exhibition in Berlin is trying to get to the bottom of the enduring appeal and uncomfortable political connotations of FW Murnau’s silent film – with free entry to those willing to make a blood donation outside the gallery.

Phantoms of the Night: 100 Years of Nosferatu, which opens at Berlin’s Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection on Friday, shows that while Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula served as the obvious inspiration for the film, the Austrian-born screenwriter Henrik Galeen changed his source material in significant ways as he moved the action from Whitby in North Yorkshire to the fictional northern German port town of Wisborg.

“If Dracula in the novel was a cunning individual that sucks blood from his victims, Nosferatu in the film becomes a carrier of the plague,” said the curator Jürgen Müller, an art historian at Dresden’s Technical University.

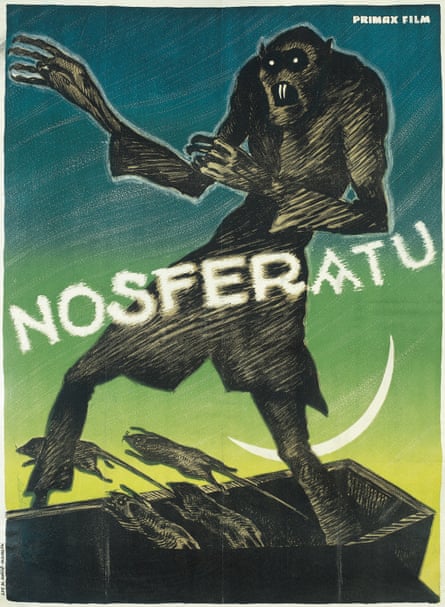

Posters advertising the film, designed by its producer Albin Grau, depicted the vampire stepping off a boat in the company of an army of swarming rats. As the phantom-like spectre enters Wisborg, he passes the town well and seems to poison it that very moment. “The vampire becomes a symbol of the epidemic,” writes Müller in the Berlin show’s exhibition catalogue, which is dedicated to the virologist and leading coronavirus expert Christian Drosten.

Contemporary audiences would have personally experienced the “Spanish flu” that ravaged the globe between 1918 and 1920, and the flea-borne typhus fever that had killed more people in parts of eastern Europe during the first world war than military action.

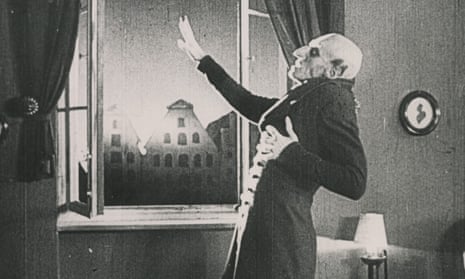

Throughout the movie, Murnau intercuts acted scenes with documentary footage of rats, hyenas and spiders. When a doctor battling the disease likens the contagion to “a polyp with tentacles”, the film shows microscopic images of a polyp’s tendrils devouring another cell.

Some advertorials promoting the film depicted the monster as a cross between a blood-sucking mosquito and an ant-eater, reminiscent of the fantastical creatures depicted by the expressionist artists Alfred Kubin and Franz Sedlacek that dot the show at the Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection, a gallery specialising in surrealist art.

“Nosferatu was the least erotic vampire you can imagine, a far cry from the Latin lovers that would grace Dracula films in decades to come,” said Frank Schmidt, one of the exhibition’s co-curators. “In Murnau’s film the vampire’s fatal bite is always only suggested, never shown. No one would want to be bitten by this creature.”

The fears that “Nosferatu” manages to bundle into its titular monster were at least in part also xenophobic and antisemitic in nature. The hook-nosed vampire’s arrival in Wisborg evokes old German conspiracy theories of Jews having caused the spread of the bubonic plague by deliberately poisoning wells.

In the film, the vampire plots his journey to Germany with the help of the estate agent Knock, played by the Jewish actor Alexander Granach. They communicate via letters featuring kabbalistic symbols and a star of David. Galeen himself came from a family of Galician Jews in the former Austrian empire, and had made his name with two films about the golem legend.

“The film plays with fears of foreigners, especially of Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe,” said Müller.

While Müller has previously written at length about the seminal film’s antisemitic undertones, the exhibition skirts over the issue fairly lightly – surprising, perhaps, given the scandal caused at this year’s Documenta arts festival by an artwork containing a vampire-like caricature of a Jewish man.

In spite of its dark allure, Nosferatu flopped at the box office. One of the first films whose marketing budget surpassed its production costs, posters and adverts were plastered across Berlin months before its release. But because the all-powerful UFA production company declined to show the film in its chain of cinemas, it was only shown at smaller venues and failed to recoup its investors’ money: three months after its release, the production company, Prana-Film, went bankrupt.

The company’s legal successor was then dragged into a copyright lawsuit with Bram Stoker’s widow, Florence Balcombe. After seven years of legal action, Stoker’s side won the case and all copies of the film were ordered to be destroyed.

With several prints already in circulation across the globe at that point, however, it survived, and Nosferatu the undead would continue to stalk the collective imagination.