Source: Schrim.de

Starting with his love for music, his falling out with Picasso, or indeed the question of which of his creative phases was accompanied by herrings.

1. “WHY DO I ALWAYS PAINT VITEBSK? THROUGH THESE PAINTINGS I CAN CREATE […] MY OWN PERSONAL HOME COUNTRY”

Small wooden houses with lopsided fences and an orthodox church with a large dome are themes that are typical Chagall images in all of his creative periods. They are scenes from his hometown of Vitebsk in what is now Belarus and that become symbols of the artist’s longing for his lost home. Marc Chagall first left the town in 1911 and with a scholarship in his pocket moved to Paris. When he returned three years later for a visit, he had no idea that the start of World War I would put a made it impossible for him to travel for eight long years. At the age of 33, after having spent eight years in Russia, he set off for Paris once again – and never returned to Vitebsk. He incorporated his memories into numerous paintings with which he created his own native home – whether he was in Berlin, Paris or New York at the time.

2. HALF A HERRING; NAKED IN PARIS

Chagall was 24 years old when he first moved to Paris, the then center of the art world. To begin with he scraped by on 40 Rubles a month provided by an admirer and patron from the Russian Duma. He had to be incredibly careful with money and this made his first years in the city very difficult. Legend has it that he often survived on just half a herring a day and that he painted naked so as not to ruin his clothes.

3. CHAGALL, PICASSO AND A DINNER WITH GRAVE CONSEQUENCES

His friendship with Pablo Picasso was characterized by highs and lows. The fact that they had shared similar backgrounds and had experienced similar success made them perfect companions but would also result in them later falling out. The two exceptional artists were friends for 20 years until a dinner with serious consequences put an abrupt end to their friendship. The exchange that led to their friendship finishing is said to have run something like this:

“When are you going back to Russia?” Picasso asked Chagall.

“After you,” said Chagall with a smile. “I’ve heard that you are very popular there [because Picasso was a Communist], but that doesn’t go for your work (…).”

To which Picasso answered: “I think it’s a business matter. You don’t go somewhere if there’s no money in it.”

This final barb hurt Chagall so much that he never spoke to Picasso again.

WHEN MATISSE DIES, THEN CHAGALL WILL BE THE ONLY ARTIST LEFT WHO REALLY UNDERSTANDS WHAT COLOR IS.

PABLO PICASSO

However, the two are also reported to have spoken highly of each other. Picasso referred to the work of his friend as follows: “When Matisse dies, then Chagall will be the only artist left who really understands what color is. I’m not crazy about his hens and donkeys and flying fiddlers and all the folklore, but his canvases are really painted, and not just various things tossed together.”

4. “THE GREATEST SOURCE OF POETRY OF ALL TIMES”: THE BIBLE

When you think of Chagall, you can’t help but also think of his impressive Bible illustrations. Chagall worked over a period of 30 years on this project that was put on hold for many years by the death of his client, World War II, uncertainty, and his need to flee; it was not to be completed until 1956. For Chagall, the Bible was the “greatest source of poetry” from which he drew inspiration for many of his works. This is all the more remarkable given that he grew up in an ultra-Orthodox Hasidic Jewish family in which the visual depiction of divine Creation is forbidden. When at a later date Chagall began to paint figuratively, a highly religious uncle is even said to have refused to give him his hand.

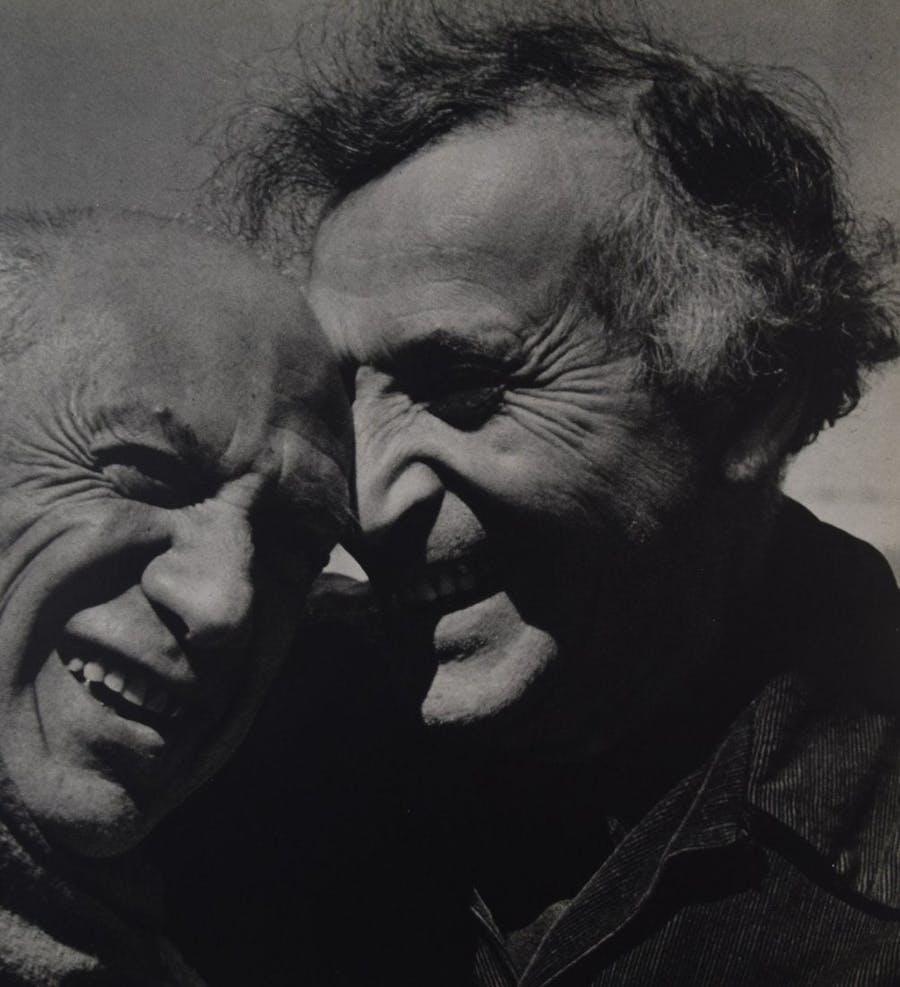

5. BELLA, BELLA, ALWAYS BELLA

March Chagall and his wife Bella shared something truly extraordinary both regarding how they viewed life but also intellectually. And most importantly they shared common memories of their hometown Vitebsk. The couple was married for almost 30 years until Bella died suddenly in 1944. Chagall expressed his deep mourning in his art: The work “Around Her” served to immortalize their love. An acrobat floats down from above holding a kind of magical ball in his hand in which the clustered houses of their hometown can be seen. Chagall places his wife in the right half of the picture using delicate brushstrokes to depict her, while she turns with a melancholy air to look at the depiction of her lost homeland. The artist himself sits at the easel with his head turned upside down. Throughout his life Bella is the protagonist of many of Chagall’s paintings and this continued even after her death.

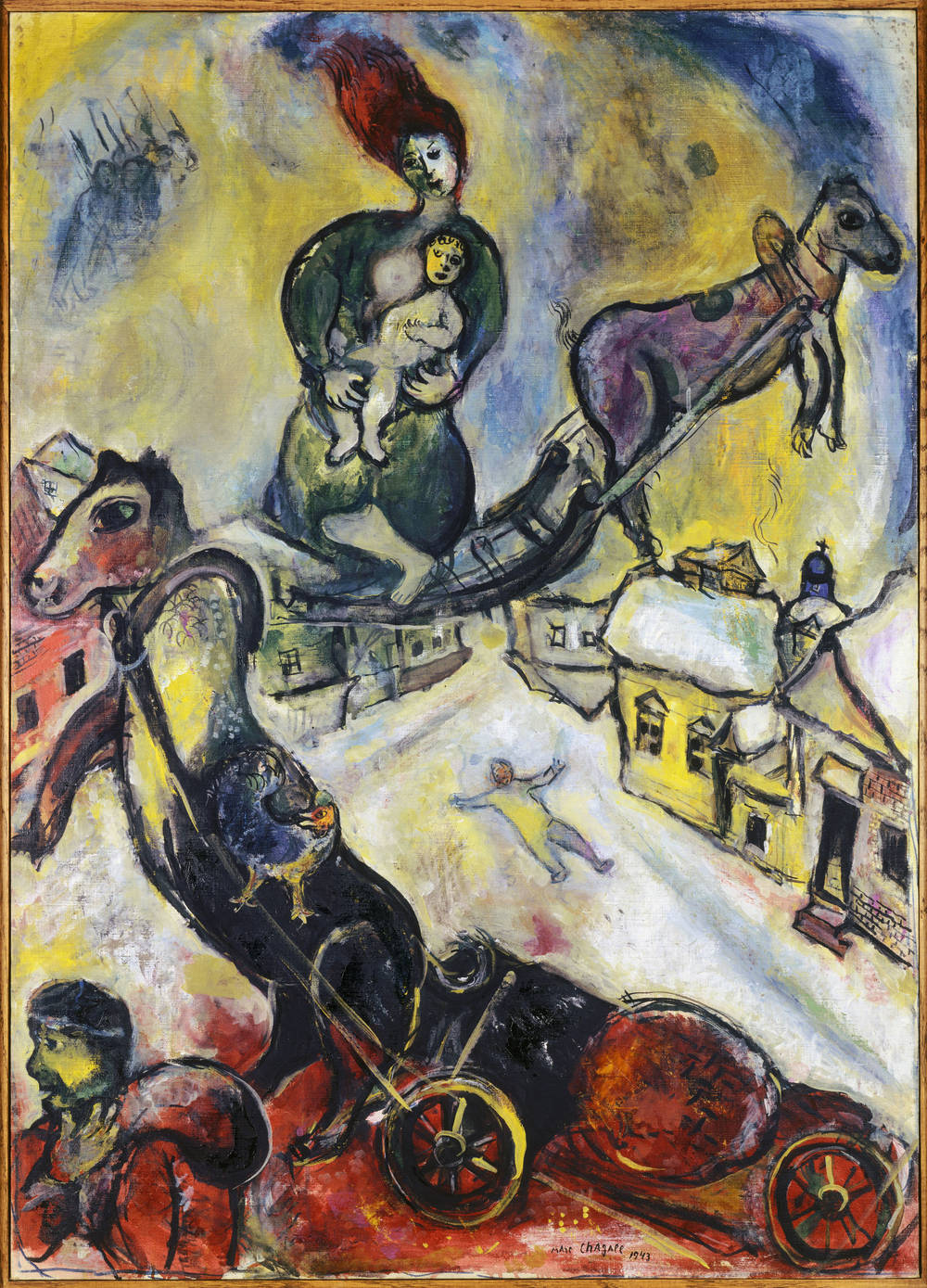

6. ONE OLD CANVAS BECOMES TWO NEW WORKS

When Chagall returned to his studio in the spring after Bella’s death, he felt especially attracted to a large canvas that he had originally worked on in 1933. On the spur of the moment, he cut the painting “The Circus People” into two halves and then painted over the original. From the one half he created “Around Her” and from the other “The Wedding Lights”. All that remained of the original composition is a winged creature with a goat’s head that raises its glass to the bride and groom.

7. OF FLOATING FIDDLERS, FIDDLES AND MUSICAL PICTURES

Music is a constant source of inspiration for Chagall. Musical images are a means for the artist of connecting with his past, his roots, and artistic experiences, and form the basis for his understanding of religion, history, and culture. He is particularly fascinated by the figure of the fiddler. The fiddler reminds Chagall of his childhood because whenever there was a celebration in the village musicians were always present. Simultaneously, the fiddle is an important instrument in the Jewish culture of Eastern Europe – and for Jews forced to leave their homeland it provided comfort and consolation. In Chagall’s works, music assumes a ceremonial and ritual importance: It accompanies important events in the life of the individual and society and encourages people to tap into their spiritual side.

8. CHAGALL GOES OPERA – IN PARIS, NEW YORK AND FRANKFURT

Chagall’s love of music is also revealed in the artist’s most monumental works; the fresco he completed for the Paris opera and murals for the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. September 1964 saw the unveiling of the ceiling painting covering an area of some 200 square meters of the Opéra Garnier in the French capital. It is dedicated to the greatest composers and their works. Shortly afterwards the Director of the Metropolitan Opera in New York commissioned Chagall with two murals “The Sources of Music” and “The Triumphs of Music” as well as stage sets and costumes for the production of “The Magic Flute” by Mozart, a musician Chagall always greatly admired.

Fun Fact: Frankfurt can also count itself lucky. After all, from 1963 to 2004 the enormous 2.55m x 4.00-meter painting “Commedia dell’Arte” graced the Chagallsaal in the complex housing the municipal theater and opera house on Willy-Brandt-Platz.

9. “IT TOOK ME 30 YEARS TO SPEAK LOUSY FRENCH, WHY SHOULD I ATTEMPT TO LEARN ENGLISH?”

In 1941, the Chagall family moved to the United States to escape persecution by the Nazis. Chagall lived in the buzzing metropolis New York for six years but never really took to it. He neither learned the English language nor did he make a point of explicitly depicting the city in his works – as was the case with Vitebsk, or for that matter France where several works featuring landscapes or city views testify to his seeking to become acquainted with the country. Although Chagall accepted several large commissions while in the States he socialized largely with other emigrants, exiled artists, and Yiddish-speaking intellectuals.

10. THE MOMA, ALFRED H. BARR JR. AND GREAT SUCCESSES

Five years after he moved to the United States in 1946 the Museum of Modern Art presented a large solo exhibition featuring Chagall’s works. It was the director of the MoMA, Alfred H. Barr Jr., who ensured that Chagall’s name was added to the list of European artists who should be given asylum in the United States to escape persecution by the Nazis. However, the show in the MoMA was by no means his first great success: Three decades earlier some 200 works had after all gone on display in Galerie Sturm in Berlin and were incredibly well received by the general public. Today, Chagall is one of the few artists to have been exhibited in the Louvre during his lifetime. And this seems a fitting end to the artistic career of the man who lived to be 97 and began his artistic journey by copying the Old Masters in that selfsame museum.