Source: The Culture Dump

By Dr. Rebecca Marks

The following work was found in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England. It was printed at Naples, in the black letter, in the year 1529. How much sooner it was written does not appear. The principal incidents are such as were believed in the darkest ages of Christianity; but the language and conduct have nothing that savours of barbarism. The style is the purest Italian.

This is the opening of what is usually agreed to be the first ‘Gothic’ novel: Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto. Published in 1764, this strange, melodramatic, and rather ridiculous story (the jumping-off point of which is a giant helmet falling out of the sky to enact a long-lost family curse), really took the literary world by storm.

Look again at that opening. What does it remind you of? Perhaps The Blair Witch Project, or Paranormal Activity: movies which assure us, from the very beginning, that the story is genuine and historic, because the footage was found in a chest in the woods, or whatever.

Well, this is exactly what Walpole is saying. He’s telling us that he found the manuscript in a random library. It’s a framed narrative, which means that Walpole isn’t claiming that he wrote it himself (which, of course, he did), but that it’s a relic from a lost ancestral past.

That opening promises to tell us a superstitious, mythical story of the kind which was believed in the ‘darkest ages of Christianity’ – the medieval period. And it’s that mythic, medieval, superstition which makes the story GOTHIC.

The word ‘Gothic’ comes from the Germanic tribes who invaded the Roman Empire in the 4th and 6th centuries: the ‘Visigoths’ and ‘Ostrogoths’. The word ‘Gothic’, though, didn’t come into parlance until the Renaissance.

The Renaissance was a period, from late-medieval to early-modern, where the arts and literature of the Classical world were revived in a Christian context.

Basically, the word ‘Gothic’ was used by Renaissance scholars as a pejorative way to describe the supposedly barbaric, primitive, medieval culture of Europe after the fall of the Romans (loosely, 4th-6th C) and before the revival of the Classics (loosely, 14th-16th C).

‘Gothic’ is, essentially, the opposite of ‘Classical’. Classical is ordered, harmonious, and rectilinear. Gothic is chaotic, discordant, and curvilinear.

The stylistic differences between Gothic churches and cathedrals and Greek and Roman temples manifest this opposition in interesting ways. Classical temples are refined and geometric. Pillars, triangles, squares, hexagons: every component fits in proportion with everything else (yes, even in Corinthian designs).

Gothic buildings, on the other hand, are more about intricate, naturalistic, excessive aesthetics. They soar upwards – in the form of pointed arches, spires, steeples – and aren’t so much interested in mathematical balance as they are instead in impressing on the viewer a sense of awe and sublimity.

So, when Walpole says that his head is ‘filled with Gothic story’, what he means is that he’s interested in narratives which defy the ordered, harmonious tragedies and comedies of Classical storytelling.

He wants fairytales, ghost stories, and folklore: fragmented, unrefined, magical, and amoral.

The Gothic, having thus entered the public consciousness via Walpole’s Otranto, developed over the turn of the nineteenth century into a highly tropey genre of art and fiction.

What you have to remember about the Gothic is that it always comes back to a romanticised idea of a lost, fragmented, past: a past where the imagination is unimpeded by enlightened Classical ideas about reason and order, and truth is instead shrouded in darkness, mystery, and magic.

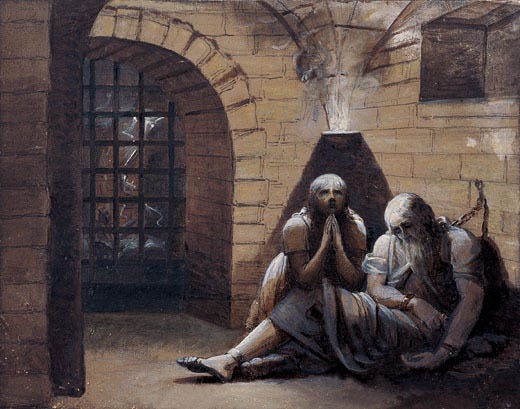

Gothic settings are always obscure or fragmented: ruined castles, monasteries, dungeons, or boundless mountains and moors.

Gothic characters are always unpredictable or supernatural: vampires, ghosts, mad scientists, crazed revengers, or heroines who just won’t stop fainting.

The Gothic doesn’t moralise. There are no conclusive or happy endings. There are only intermingled, chaotic narratives of fear, desire, and transgression.

One defining feature of the Gothic is that idea of the framed narrative. This is why Gothic novels are filled with letters, diary entries, found manuscripts, dreams, and reported speech, and Gothic paintings are full of so-called ‘liminal’ or negative spaces (windows, graveyards, ruins, dungeons, corridors, shadows). The idea is that we, as consumers of the Gothic, can never be sure about the truth because it’s always shrouded in degrees of separation.

This heightens the sense of uncertainty, which makes us feel scared, or excited, or (in the case of Emerald Fennel, directing the trailer for Wuthering Heights) horny.

So: a brief summary of what we’ve established so far.

- The word ‘Gothic’ originates with the Germanic tribes, Ostrogoths and Visigoths, of the 4th-6th centuries.

- When Renaissance scholars revived the Classics, they retrospectively termed the ‘Goths’ the barbaric destroyers of the Roman Empire.

- The art and architecture of the ‘Gothic’ is, in general terms, opposed to those of the ‘Classical’ enlightenment.

- In 1764, Horace Walpole became interested in fantastical narratives, and structures his novel The Castle of Otranto around themes and motifs he associates with the Gothic: ruins, amorality, framed narrative, magic.

- And so, the Gothic genre was born, and popularised over the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries.

This is only a very generalist history, though. The Gothic is a bit like an octopus. From Walpole, it starts reaching out in all directions.

We get female-centric Gothic novels, written by women for women (Clara Reeve, Ann Radcliffe, Charlotte Dacre), which become a safe space to explore feminist themes of emancipation and imprisonment, sexuality and fear.

We also get so-called ‘Orientalist’ Gothic: so, that’s narratives and imagery which use the East (sometimes the Middle East or Turkey, but sometimes even just Italy or Spain), as a backdrop for evil or excess.

The Gothic is also profoundly tied up in the divide between different forms of Christianity. Often, it’s written by a German or English Protestant, but set in a Catholic context. Protestants considered Catholics to be superstitious, ritualistic, and idolatrous – and you can see how that might turn over into supernatural fantasy pretty quickly. Angels, demons, saints, sinners, and so on and so forth.

And don’t even get me started on Vampires. There’s a whole genre of Gothic fiction – starting with Lord Byron, and extending to Bram Stoker (and I guess eventually to Anne Rice and Stephanie Meyer) – dedicated to the idea of the Nightmarish, sexually transgressive creature which enters the bedroom and penetrates the body with its, err… teeth.

So, with all this said, here’s my curation of Gothic literature which I teach to students when I cover the Romantic period in England. Because of this, I will have missed out your favourite French, German, or American Gothic novelists. Apologies.

Moreover, this list only goes up to the 1820s, which marks the end of Romanticism (death of Lord Byron) and the beginning of the Victorian era. Which of course – with Dickens, Wilkie Collins, the Brontës – has its own peculiar kinds of Gothic (metropolitan, crime fiction, psychological horror).

There is no Carmilla (Le Fanu) or Dracula (Stoker) on this list. You get The Vampyre (Polidori) instead. Enjoy.

1764 – Horace Walpole, The Castle of Otranto. The origins of the Gothic genre. Walpole was really on one when he came up with this – goofy, weird, camp.

1777 – Clara Reeve, The Old English Baron. A moralising response to Otranto.

1786/7 – William Beckford, Vathek. Orientalist, Faustian narrative.

1794 – Ann Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho. Winding, meandering epic. Radcliffe is ultimately allergic to ambiguity.

1796 – Matthew Lewis, The Monk. Highly-sexed gender bending and ‘Nunsploitation’. Violent, macabre, and eminently readable for modern audiences.

1798 – Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Naval Gothic. Defies interpretation.

1806 – Charlotte Dacre, Zofloya; or, The Moor. Sexy, Orientalist Gothic. Heroine falls in love with a figure who may or may not be Satan.

1810 – Percy Bysshe Shelley, Zastrozzi. Shelley’s first publication. Atheism, revenge, seduction, imprisonment, etc.

1813 – Lord Byron, The Giaour. More Orientalism, this time unsurprisingly from Lordy B. Vampire narrative with the subtitle ‘A Fragment of A Turkish Tale’.

1817 – Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey. Playful and good-humored parody of the Gothic.

1818 – Mary Shelley, Frankenstein. Maybe God stays in Heaven because he too lives in fear of what he has created.

1819 – John Polidori, The Vampyre. Polidori was Byron’s doctor and he apparently based the vampire on Lordy B himself.

1820 – Charles Maturin, Melmoth the Wanderer. Another Faustian narrative. Not altogether dissimilar from Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray.

1824 – James Hogg, Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. Differing accounts, confusing narrative, a criticism of Calvinism and all-round Scottish romp.

1826 – Mary Shelley (again), The Last Man. The first post-apocalyptic novel, maybe?

Oh, and by the way, the GOTHIC is by no means just a literary genre – not at all. I’ve illustrated this article with some of the most important Gothic paintings and painters in the Romantic period: Henry Fuseli, William Blake, Philip De Loutherbourg, and of course, Caspar David Friedrich!

In Gothic art, the very same tropes apply. Isolation, ruin, repression, darkness, monsters, and ambiguity. The most famous is Fuseli’s Nightmare. There’s a direct line from that painting to the most recent Nosferatu, directed by Robert Eggers.

You have only to glance at the shelf of your local Waterstones (or Barnes and Noble, for the Americans) to see that the Gothic — or, at least, the descendants of the Gothic — is alive and kicking.

I’ve never seen more front covers emblazoned with bat wings and blood and devils in all my time as a literature student. I see curated shelves of books entitled ‘Dark Academia’, ‘Vampire’, ‘Romantasy’ everywhere.

What these newfangled stories have in common is that they aren’t remotely newfangled at all. They have the same basic Gothic themes — like the continuity of the past in the present, fear and desire, amorality, atheism — that people were loving in the eighteenth century.

So, if you want something really shocking, put down ACOTAR, and go pick up The Monk.